Robert Venturi and the Dilworth House

Looking at the renderings, you get the feeling that it's not even about the condo tower any more. The third scheme struck me as the most unbuildable - and the most rich with ideas. This proposal is for an 11-story, 50-unit rental building that would sit in the yard behind the Dilworth House. Residents would enter from Randolph Street, rather than from the Dilworth House's Sixth Street address on Washington Square. The bottom three floors would serve as a parking garage, but I can't imagine how Venturi expects to squeeze the turning ramps and parking spaces into such a small footprint. Nevermind the other structural problems.

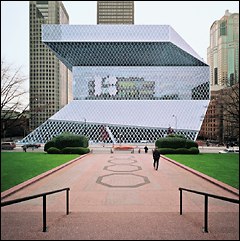

But, forget practicalities. What's interesting is that Venturi's Scheme No. 3 reprises the glass facade from his unbuilt - and much maligned - Philadelphia Orchestra project. The tower's Washington Square facade has the same rhythmic march of vertical elements, the same schematic outline of a peaked, A-frame roof embedded in the glass facade. Venturi knows that Philadelphia will never let him build this glass tower, just as the city didn't let him build a home for the orchestra. Venturi has never gotten over the way the orchestra and city blue bloods dissed him with the orchestra project. So, by riffing on the rejected design in this Washington Square project, he is effectively giving his opponents the bird - rejecting them, before they reject him. That's my reading of it, anyway.

For those of you who have not been following every twist and turn of the long-running Dilworth House saga, here's the backstory, short version:

A couple of years ago, developer John Turchi bought the colonial revival house that former Mayor Richardson Dilworth had built for his family in 1957. Dilworth, who is among Philadelphia's greatest mayors, constructed the house on Washington Square to demonstrate his commitment to reviving Society Hill, which was then a decaying and depopulated slum. Unfortunately, Dilworth had to tear down two real colonial houses to build his fake. (But since his wife was on the historical commission - no problem.) Nevertheless, his commitment to Society Hill was genuine.

The neighborhood made a historic comeback. Dilworth and his family lived happily in their fake colonial house. When the Society Hill historic district was created, the house was listed as a "significant" building - the highest ranking for historic buildings. It means it can't be torn down except in extreme circumstances. Turchi also intended to live in the house, but then changed his mind. The developer, who is currently converting the AAA garage on 23rd Street to lofts, decided he would tear down the house and build a 13-story tower.

He was clever, too, and hired Philadelphia's most famous architect to design it, hoping to win the sympathies of the city's architectural community. That strategy worked with the architects - but not the Historical Commission. They refused the demolition permit for Scheme No. 1. While the commission acknowledges that the fake colonial is merely average as a work of architecture, they believe it is worth preserving as a living, breathing relic of Philadelphia's modern history.

Turchi and Venturi don't give up easily. Venturi has now come up with two more schemes. Scheme No. 2 preserves the facade of the Dilworth House inside an arcade of the new tower. But get this: Venturi would tear down the facade first, and rebuild it in a slightly different location. It might be the first time that a fake of a fake was subject to a facadectomy.

Just in case the facadectomy bombed, Venturi was ready with Scheme No. 3. In this version, the house gets saved, but the neighborhood gets shafted. Turchi has proposed an 11-story tower. The bottom three floors contain the parking, and the 50 one-bedroom units are stuffed onto the seven highest floors. Surely Turchi can't be serious? Actually, it's an old strategy: Present a really bad design so that the one that was only middling bad begins to look good.

Daniela Voith, a member of the commission's architecture subcommittee, had the courage to say so: "It feels like a threat," she told Turchi.

Absolutely not, Turchi replied.

I believe I saw a smile cross his face.

In the end, the subcommittee reaffirmed its earlier decision: No demolition of the Dilworth House. But it said it would consider Scheme No. 3 if it is developed further. I can't wait for Venturi's next punchline.